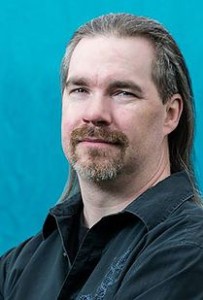

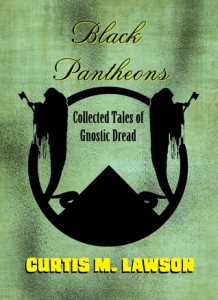

This month, I asked author Curtis Lawson (It’s a Bad, Bad, Bad, Bad World) to talk about his writing process. I’m about halfway through his new short story collection, Black Pantheons, and am duly impressed, so I figured the world should hear more from this talented author. Black Pantheons is available now on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Here’s Curtis, in his own words!

Short stories have always been hard for me. They demand, in many ways, storytelling of a much more engaging and clever nature than novels. The telling of short stories is a delicate balancing act of establishing character, atmosphere, and plot within a limited space. If too much is revealed, the pacing can easily fail. Reveal too little, and you risk a disinterested reader.

In short fiction, it’s imperative to capture your audience straight away, enrapture them in the vaguest glimpse of your world, make them sympathize with a passing stranger, and deliver some memorable manner of resolution.

There are three key factors, I believe, in creating a winning short story. The first is economy of language. The second is choice of character. Lastly, the situation and conflict must be able to survive in a vacuum.

I know many authors will argue that short stories should be written by the seat of your pants. I’ve never had success with that method. The discipline of the word count is always at odds with my natural ramblings, so I approach short fiction much like I do scripting comics.

The first decade or so of my writing career was focused on comics and graphic novels. One of the realities of that industry is the firm page count. Comic publishers want books between twenty-two and twenty-four pages per issue. Your creative vision for a thirty-five page story will never warrant you an extra ten pages, unless you’re self-publishing. As such, I grew accustomed to writing in these confines.

When scripting a comic, I would break the story into scenes and budget out a certain number of pages to each scene. Early on, I learned visual shorthand techniques to establish character and mood in the limited confines of the comic page. Dialogue was written with economy of space in mind. Every word spoken would have to perform multiple functions – convey information, forward the plot, and establish tone and character. There was simply no use for a word that served only one of those functions.

These are the lessons regarding economy of language that I brought with me when I started writing short prose. I first determine plot and tone. Next, I set a goal of my word count. After that, I break the story into scenes and budget a rough percentage of my word count as each scene warrants.

When the time comes to actually write, I do my best to make economic use of language. My writing has often been described as cinematic. That is in no small part due to my background in visual storytelling. In prose, I try to use strong imagery and visual short hand to serve multiple functions, very much in the way I would with comics.

The second key to writing good, short fiction, as I stated above, is choice of character. In this regard, I think of the words of Stephen King, that a short story should be a dance with a stranger. Your character in short fiction must have barbs about their person, ready to hook the reader’s mind. This could be something as superficial as a distinct manner of speaking, or as intimate as the troubling inner monologue of a diseased mind. The trick is showing just enough to make the reader say yes to the dance. In a novel, you want your readers to fall in love (or hate) with your characters. In a great short story, you should strive for lust. You want them thinking of the character days later, wondering what might have been if they had had more time together.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, is for your story to be capable of surviving in a vacuum. That vacuum is the unwritten void around your narrative. As a writer, you choose specific, extraordinary events, and decide they are special enough to write about. If the story is to stand as a tiny snippet into imagined lives, it must be strong enough to resist the vicious gravity of the reader’s mind. The here and now must be so deeply intriguing that the reader forgets that there is no before or after. Paradoxically, you need to manipulate the reader into yearning for those non-existent elements outside of the story. To put it simply, resolve the story, but always leave them wanting more.

So there you have it, my personal philosophy and routine for writing short stories. Nearly every piece in my collection, Black Pantheons, was written in this same manner. Down the road, I may experiment in contradiction to this, but to date, this works for me. Hopefully the stories I’ve written work for others.

See? Told you this guy was good. You can learn more about Curtis and his books at his website, https://curtismlawson.wordpress.com/.

What ever happened to zombie moose? Tonight we explore that and more as Duane Coffill joins us to talk about his work, the work of the Horror Writers of Maine and their premiere anthology

What ever happened to zombie moose? Tonight we explore that and more as Duane Coffill joins us to talk about his work, the work of the Horror Writers of Maine and their premiere anthology